By Elliot Worsell

BACK when first imagined as a retirement plan, the only thing pursuing Michael Conlan in his attempt to master marathon running was boxing, the sport he had left behind. He expected to hear its heavy breathing in his ear, and see its shadow left and right, yet still, despite these reminders, it was expected to be a joyous occasion, this run. It would be joyous not only because Conlan could be certain of his ability to stay ahead of his pursuer – that is, boxing – but because now, having achieved everything he had wanted to achieve as a boxer, these runs in retirement would be more akin to victory laps, with all the hard work and suffering behind him, losing more and more ground with each mile.

Yet, of course, rarely is life either that simple or indeed that straight. In fact, and to prove this point, when tackling and completing the Manchester marathon at the start of April, it was not boxing Michael Conlan found himself running from but instead something else: pain.

“I was at the lowest point I have ever been in my life,” Conlan said of the three months following his loss against Jordan Gill in December. “That’s not just because of the loss, but also everything else that was happening at that time. It was all to do with family and it’s been very, very tough. I have felt proper depression, to be honest with you. It’s been quite hard actually and I feel emotional even saying that to you. But that’s just life, isn’t it?

“I think joining the running club gave me a better outlook on that: life. Mentally, it helped me so, so much. The training for it was probably harder than any boxing training I’ve ever done. These people get up at five o’clock in the morning to go out running and yet they’re not even getting paid for it. I said to them one day, ‘There’s something wrong with you. I’m getting paid hundreds of thousands to fight and you lot aren’t being paid a penny to do this.’

“They helped get me through a very dark time in my life. I would never say I was suicidal, but I was just really, really low during that time. I have two kids, so I would never do something stupid like that, or even say something stupid like that, but I was in a really dark place.

“As I keep saying, though: it’s life. These things happen. You’ve just got to run through the muck until you get back on dry ground.”

The feeling when signing up for the marathon was that Conlan, coming off back-to-back defeats in the ring, was either retired or, at best/worst, in a waiting room eyeing the door to that room. His aim, meanwhile, was to complete the marathon in under three hours, which of course he did, crossing the line at a time of two hours and fifty-five minutes.

Interestingly, too, it was somewhere during those two hours and fifty-five minutes, or, more specifically, when hitting the wall at mile 24, that Conlan realised marathon running was not for him. Not now anyway. He could keep up with the best of them, that was not the issue, yet in deciding to do the race and in both preparing for and completing it he had now come to understand exactly what it was he was trying to escape.

“I’m going back to boxing,” he said. “Fuck that running stuff at the minute. It’s tough. I’d rather go back and do what I want to do and what I believe I can do.

“If I was done, my own family would tell me. They would say, ‘Enough is enough.’ My own brother (Jamie) is so close to me and manages me. He would be the one to say, ‘Stop it.’ He doesn’t like to see me fight because we’re brothers. It was the same with me when he was fighting. I didn’t want to see him fight anymore after a certain point. Even when I’ve been winning fights, he has said, ‘I don’t want to see too many more,’ because of how hard the fights can be at times. If he were to say to me, ‘Mick, come on, it’s time to stop, there’s no more here,’ then I would say to him, ‘Sure, no problem.’

“He has said that in an ideal world he doesn’t want to see me go through it anymore, but he also understands my reasons for carrying on and realises I still have something to give. He said, ‘If you want to go again, that’s up to you. I’m not going to force your decision.’ He knows I have a lot left in me and I also have something to prove to myself now. I’m not proving anything to anyone else. It’s just me.”

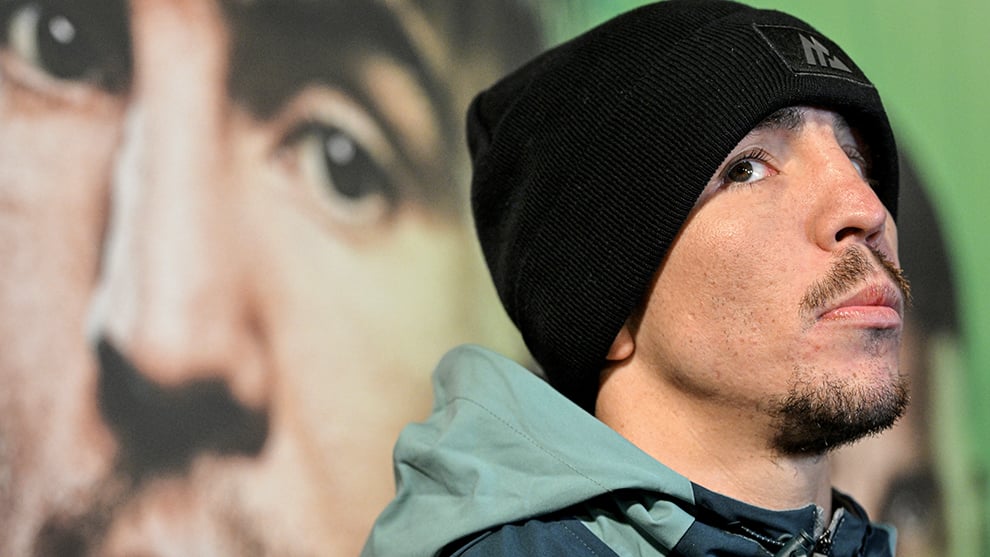

Conlan in the changing room

Naturally, when so much of a boxer’s ability to do what they do is predicated on an equally impressive ability to convince themselves they are bigger, stronger, and faster than everyone else in the world (that is, suspend their disbelief), sometimes the most dangerous opponent is not the one standing opposite them in the ring but the one staring back at them during bouts of shadowboxing. It is this person, after all, who must protect them, both from reality and from the views of outsiders, and also at times comfort them, by whatever means necessary, during periods of doubt and hardship. This relationship, for a boxer, is often as negative as it is positive, yet Conlan has, with experience, learned to discern the difference between legitimate excuses and ones designed only to protect him and prolong his delusion.

“People don’t see what’s going on in your life, yet they can have an opinion on what you should do with your life – in terms of giving up your profession or not – because we do this thing in a public forum,” he said. “It’s madness. All these people get to comment on your career, but it’s only the minority who know what they are talking about. The majority talk shit and just want attention.

“Nowadays you can’t have two losses on the bounce and come back. It’s impossible. You’re ‘shot’; you’re ‘done’; you’re going to ‘do damage to your health’ and all this bollocks. The Leigh Wood defeat was bad – I get that, because of how it went – but in both the (Luis Alberto) Lopez fight and the Jordan Gill fight I was finished on my feet. I was conscious. I wasn’t fucking knocked out. It wasn’t some thunderous knockout where you then go, ‘Fucking hell, he needs to take a look at his life here.’

“I’m very aware of boxing. I understand boxing. I have been around boxing my whole life. It’s something I’ve been very successful in and I’m probably in the one per cent of people who have made enough money from the sport to walk away and be set for life. I don’t need boxing. I started my own promotional company with my brother, and that’s now beginning to flourish and grow massively; so that’s one avenue I can walk into with no problem. I also have my own fucking beer which has been launched. That’s another avenue for me in retirement. Streams of income are plenty for me. It’s not like I’m dependent on boxing for that.

“But it’s not about the money, is it? It’s about proving to myself that I can still achieve something in this sport. Who knows what will happen? Sometimes you can be right and sometimes you can be wrong. But why the fuck am I going to stop trying when I know I still have it in me?”

That final concession will stand Conlan in good stead going forward, of that there’s no doubt. It shows, at the very least, a healthy grasp of reality, as well as the kind of humility that is only ever the symptom of a punishing, foundation-shaking loss. Not only that, Conlan, 18-3 (9), has reasons. Reasons to think like this. Reasons why certain things have happened. Reasons why running has of late been a form of therapy rather than something done in celebration.

“There was an awful lot of family stuff – personal stuff – going on before my last fight,” he said. “It’s nobody else’s business, I suppose, but I shouldn’t have been anywhere near a ring that night.

“That’s life, though, isn’t it? You just get on with it, continue with training, and suddenly the fight arrives. I trained for six weeks with a new coach (Pedro Diaz) and had so much personal shit going on, so nothing felt right. But you make decisions and you live with the consequences.

“I don’t believe that was the true Michael Conlan and I know he is still there. As a boxer, you know in sparring when you’re getting manhandled by guys you should be controlling, but I was handling guys who were 135 and 140 pounds. That wasn’t the problem. It was life. My head wasn’t in it.

“Before that Gill fight was even made, it was said to me, eight weeks out, ‘What about Jordan Gill?’ and I said to Jamie, ‘No, I don’t need that fight now. That’s not the right fight.’ I had to get a new coach – I hadn’t even trained with Pedro Diaz yet – and I would have six weeks training over there (in America). I knew it wasn’t the right fight, but we rolled the dice and that’s what happened. Hindsight is a wonderful thing. Remember: nobody knew what Jordan Gill was going through until after the fight, either.”

Michael Conlan (Getty Images)

In boxing, you will now and again find an unlikely connection between a comeback and running away, despite how conflicting the two things appear in isolation. For Conlan, for example, an Irish star famous before he had even thrown a punch professionally, there is an argument to be had that his best route to coming back is to first get away. Not run away, perhaps, but certainly do away with all the pressure and attention he finds when boxing at home, in Belfast, the city with which he has, since his amateur days, been synonymous.

“I’m thinking October or November and I’m thinking America – maybe New York,” he said. “Let’s get away for a moment. I’ve just suffered back-to-back defeats in The SSE (Arena, Belfast). I know I can still sell a ticket there, and can still sell it out, and obviously that’s part of the value of Michael Conlan, but I also know I can do a ticket in New York. Going there is a way for me to take the foot off the gas and have one fight to come back on. Let’s be honest, right, I’ve lost twice by fucking stoppage. I need to have a comeback fight. I need to get a win. Get the confidence back and get back in the swing of things. That’s what I need.

“I’m also going to have to change everything up again. I will say that Pedro Diaz was probably the best coach I’ve ever trained with, but it came too late in my career, probably. Pedro wanted me to box orthodox the whole fight (against Gill), but, if you look at my career, although I’ve switched, I have predominantly fought as a lefty.

“We just didn’t have enough time together to work on ideas. I think it’s too late in my career to be trying to make big changes, so I’ll probably come back to the UK and base myself there. I’ve got a few coaches in mind, but that’s why I’m saying October or November for my return, so I have a bit of time.

“I’m going to go back to 126 pounds well. I shouldn’t have been at 130 for the last one, but it was eight weeks’ notice and I was told Gill was now up at 130, so I went for it. It was the wrong move.” He paused, then laughed. “Why the fuck did I do that?”

At 32, Conlan, a featherweight, now finds himself both young and old; old enough to be called “shot” or “faded” in his line of work, yet still young enough to believe otherwise and value, quite rightly, the opinions of those who see him daily over those who watch him only for entertainment; old enough to have now shaken off, like rain from an umbrella, any dreams of making history or changing the world, yet still young enough to adjust these expectations and achieve something noteworthy nonetheless; old enough to accept the unreliability of confidence, yet young enough to still be shocked and unsettled by the feeling of it ebbing away.

“After two defeats your confidence is a bit knocked, there’s no point denying that,” Conlan said. “I can sit here and go, ‘My confidence is just fine. I know the reasons for the defeats and I am going to put things right.’ But I’m not saying that. There are reasons for the defeats, yes, but when you lose, no matter the circumstances, you do look at yourself and go, ‘Fuck me, am I as good as I think I am?’”

In certain moments the answer to that question will be “no”, quite understandably. Whereas in other moments, either when Conlan is out running, or reminding himself of all he has achieved in the sport, as both an amateur and pro, he will be more inclined to say, “Yes, I was that good; yes, I am good.” Sometimes, you just need reminding, that’s all. For confidence is, like a muscle, something liable to atrophy if not given the right amount of attention and care.

“This is the longest I’ve gone without boxing in my life,” said Conlan. “I haven’t been anywhere near a gym and have not even thrown a punch since my last fight. Only recently did I start trying to shadowbox – not properly, but just a few punches around the house – and think about boxing a bit more.

“That time away has kind of freshened me up in a sense and made me go, ‘You know what? There are still things to do here. There’s still a route to a world title.’”