By Elliot Worsell

PART I

TEN YEARS on, it is clear now that it became a numbers game, the rivalry of Carl Froch and George Groves. In the first installment, there was the promise of two right hands in round one and then six months later it all ended in round eight with one right hand witnessed by 80,000 fans. Meanwhile, between those two flashpoints there was special importance placed on the number six by Groves’ coach, who believed Froch was so haunted by the events of round six in the pair’s first fight that he now couldn’t bear the thought of that number, as well as the number 31, which, to be honest, remains a mystery even to this day.

There were also other numbers of importance; increasing numbers, that is, both in terms of entourages, sponsors, and figures in various bank accounts. According to a report in the Daily Mail, the 2014 rematch between Froch and Groves was at the time declared the highest-grossing fight on British soil in history, with the largest ever purse: £10million. (Froch taking home £8m and Groves £2m.) In addition, the newspaper’s analysis of the finances showed that the total income from the night was more than £22m, more than any other fight in Britain, while the official Wembley Stadium crowd of 77,000 – rounded up at every turn by Carl Froch – beat the previous British record of just over 70,000, set in 1933 when Jack Petersen beat Jack Doyle at White City. Gate receipts were reported as £6m, and the pay-per-view sales on Sky Sports Box Office surpassed the 900,000 mark, ensuring, at a price of £16.95, the event would provide a UK take of just over £15m. The international television take, meanwhile, was around $1m (£580,000), and then there was sponsorship, which poured around £250,000 into the pot, and merchandise and hospitality sales, which added £250,000 to a grand total of £22.3m.

As crazy as it sounds now, there had once been a feeling that Froch was reluctant to take the rematch. Such was the nature of their first fight, you see, a fight shrouded in controversy, many believed that he would avoid Groves almost just to spite him and that, had it not been for the IBF getting involved and ordering a rematch, it may have never happened at all.

Yet Froch, despite the scrutiny, remained committed to settling a score. Not just that, the Nottingham man would actually beat Groves to the punch by arriving first at Wembley Stadium on May 31, 2014.

Indeed, no sooner had the IBF and WBA champion’s car parked inside the stadium that night than he confidently stepped out, swigged from a plastic bottle of water, and began at once to wander, choosing not to head to his changing room but instead towards an opening between two stands. Slowly, with each step, Froch was set to discover more and more red seats visible through the gap between stands and all of a sudden the noise of the crowd, still filling up at half past seven, increased tenfold as he appeared on the big screens. Up to now this moment had presented itself to Froch like a smile, wide and expressive and ostensibly welcoming, yet the second he was seen on screen the mouth fully opened, revealing to Froch a set of brown, rotten teeth. Its subsequent cackle – or: the boos of fans – was then the soundtrack for the champion turning away and seeking the relative serenity of a changing room.

Groves, for his part, arrived a little later at 7.50 pm and, owing to either a lack of time or sheer disinterest, had decided against taking a peek at the crowd expecting violence in a few hours’ time. Instead, Groves sought to make his world smaller. Which is to say, upon entering his changing room he, and his team, covered each of the cameras they found suspended in the corners of the room with either towels or blue tape. (Froch, in contrast, left them alone, thus giving Sky Sports, the fight’s UK broadcaster, an insight into whatever it was he was doing backstage. This, in retrospect, was either an omission on his part or a sign of him being totally comfortable.)

Twenty-four hours ago, this same away dressing room had been full of Peruvian footballers gearing up for a friendly against England and its sheer enormity, especially given the jarring switch in sports, was almost overwhelming. Normally home to a squad of footballers, the exact same room now played host to only a single boxer and his small, but admittedly expanding, team. There were, as if to remind us of the change, numerous numbered pegs around the perimeter of the room used to hang matchday shirts, as well as physio tables used to treat the sore limbs of overpaid superstars. There was also a flip chart in one corner of the room, typically employed by managers to plot the downfall of the opposition with a marker pen.

Paddy Fitzpatrick, who would later do similar, shadowboxed in the middle of the room once arriving. His eyes were alive with anticipation and he yelled, for no apparent reason, “Vaya con dios! Vaya con dios!” The rest then smiled, loosened up; nerves were shaken from rigid bodies and permission to find enjoyment amid trepidation was granted.

For Sophie Groves, however, there was more at stake, something plain to see when she entered the room at 8.04pm. Heading directly to her husband, who was sitting on a bench, she kissed him; any comfort given to her as a gift rather than self-produced. “It’s nice in here,” she said.

“Yeah,” replied Groves. “Lovely and big.”

“Mum’s good, Dad’s good. Everybody’s happy up there in the Royal Box. There’s lots to drink.”

George smiled the kind of smile only she could steal from him at a moment like that.

“Is Garvey up der?” asked Fitzpatrick.

“Yeah, he’s good,” said Sophie. “Dressed very smart. My friend’s got an eye on him.”

“Tell her he’s taken. Wife an’ a couple o’ kids. Don’t go ruinin’ my youth.”

Groves smirked. “He’s got a career, more importantly.”

Cognisant of his own, the super-middleweight then rose from the bench, inspected his speakers, and began to play around with his phone, tweaking the night’s pre-planned playlist. The first song to then play, “The Spell” by Alphabeat, started in due course and Sophie, briefly alone, struggled to fight off the emotion of it all as she remained rooted to the bench. To compose herself, or simply occupy hands prone to trembling, she applied some lipstick.

“This is it now,” said Groves, to both his wife and trainer. “No more people need to be coming in here.”

With that his wife hurried to mention a couple of people keen to visit the changing room afterwards, but Groves, not yet knowing whether he would still be the same man by that time, for once seemed disinterested in what she had to say. To even so much as think that far ahead seemed dangerously presumptive; an exercise in futility; tempting fate.

All they had, both knew, was the here and now and, at 8.09 pm, when Groves rested his head on his wife’s shoulder, he did so in a way that suggested it was now the boxer, and not the boxer’s wife, who was wanting to surrender to the emotion of it all. Drawing strength, it seemed, from each other, it was as if only her shoulder was keeping the boxer intact and only the banality of their conversation – about clothes, about hair – was holding back tears. “You look amazing,” he said.

Three days earlier, Groves explained to me, with an unnerving level of honesty, “You walk a tightrope of emotion for every fight. You’re on the verge of tears in the changing room, constantly, as the fight draws closer. It could be anything that sets you off. It could be a song or it could be a phrase. It could be a face or it could be a text. So long as you catch yourself, you’re fine. But it will always be there.

“Ultimately, I’m the fighter. I’ll never forget that now. As ignorant as it sounds and as harsh as it sounds, I’m the cunt that has to take punches. When it all comes crashing down, whether people care about me or not, I’ve still got to be the person who lives with it. And that’s the hardest thing. I appreciate everyone I’ve got around me, but, to a certain degree, I’d love to be able to keep them all at arm’s length.”

It was a necessary self-centredness, I suppose, with certain allowances made by those who grudgingly accepted it as a prerequisite of his vocation. Moreover, there was an undoubted bravery to such self-awareness and honesty and a boxer’s bravery, one comes to learn, is one of the few things about them that is not later deformed by either time, a shift in context, or some newfound insight and maturity on the part of any observer. Whereas their intelligence or morality, for example, is often reconsidered as time goes by, never does the bravery of a boxer become questioned or undermined in quite the same way. A boxer’s bravery, after all, is an uncommon valour, something you don’t see every day. The bravery of a boxer at ten years of age – whether it is demonstrated in a fight or even just preparing for one – can be the kind of bravery most men and women go their entire lives without ever exhibiting. In this instance, George Groves, by virtue of just holding it together ahead of a fight in front of 80,000 fans, displayed courage beyond compare; extraordinary even in the world in which he is known, famous, and revered.

Froch and Groves hit the scales (CARL COURT/AFP via Getty Images)

PART II

At 8.12 pm, two metal chairs were dragged into the room by Barry O’Connell, a strength and conditioning coach, whereupon the boxer whose hands were soon to be wrapped made sure they were positioned back-to-back. He then sat on one of the two chairs and rested both his weapons on the bridge between them as his trainer, Paddy Fitzpatrick, stood over him and began the process of wrapping. As ever, and owing largely to superstition, the right fist was the first to be wrapped and George Groves, once happy, moved this fist towards the onlooking inspector. “No, no, you do both first,” he said. “Then I’ll sign them.”

With numerous strips of tape hanging from a nearby table, Fitzpatrick now grabbed one and got to work on his boxer’s left fist. A simple, natural, instinctive process, he would even allow himself a fleeting glance at the television showing footage of an undercard fight between lightweights Kevin Mitchell and Ghislain Maduma. “Is it true Mitchell missed de check weigh-in dis mornin’?” he said to nobody in particular.

“Yeah,” said Groves. “Don’t know how. It’s not hard to make it. He must’ve put on more than ten pounds overnight.”

“So it’s not an eliminator now?”

Lee Meager, the man sent from the Froch camp, then butted in. “It is still an eliminator,” he said, “but only for the African.”

“I see,” said Paddy. “Did you see (Anthony) Joshua? Any good?”

“Yeah. Still a baby, though. Needs a workout.”

“First round?”

“Yeah.”

All done by 8.29 pm, Groves was quick to offer his wrapped fists to both Meager, who put his hands on them and nodded his head, and the inspector, who scrawled “BBBOFC” on each of the casts. “I’m goin’ to wander an’ have a sniff outside,” Fitzpatrick said. “Dat okay?”

“Yeah,” said Groves, content to fill the silence left by his trainer’s departure with “Loose Fit” by the Happy Mondays. Bobbing his head to its beat, he now turned towards the television to watch Mitchell stop a troubled Maduma in the 11th round. As he watched, he said nothing. He simply sipped from a bottle of water and listened to the advice of Kalle Sauerland, his new promoter, who excitedly said the kind of stuff always more important to the person saying it than the person hearing it. Of more interest to Groves, it appeared, was his phone and, specifically, its playlists, which he used to distract himself both from what he was seeing on screen and the asinine chat in the room. Finding “Electric Feel” by MGMT, he called for yet another trip to the bathroom and grabbed a packet of Calvin Klein boxer shorts from his suitcase. In a flash, he and the doctor again disappeared.

Now down to just his boxers and a T-shirt, Groves, upon his return, sat on a chair and put on a pair of black Puma socks. He then slipped his right foot into a white and blue boxing boot and pulled the laces tight. Real tight. However, rather than go on to tie them, he just as soon stopped, got to his feet, and rushed to fetch his suitcase by the far wall. Pulling from it his wedding ring, he retreated once more, this time holding the ring in his mouth. “I was going to remind you,” said Phil Sharkey, who, having been snapping away behind his camera, would now watch Groves release the wedding ring down the blue lace of his left boot and wait for it to settle. Only then did he start to cross his hands and secure his foot in the boot. Only then was balance restored.

Fitzpatrick, meanwhile, re-entered the room to see James DeGale, Groves’ old rival, appear on the television screen. Seeing him, he would offer no more than a sly grin, whereas Groves, although distracted, went one better and muttered “ah-ha”. He then watched his erstwhile gym mate prowl the ring ahead of a fight against American Brandon Gonzales, with his interest stretching no further than that. In fact, caring not who won, he was soon to turn his back on DeGale altogether, kissing his gold boxing gloves necklace and nodding repeatedly to The Stone Roses’ “I Wanna Be Adored”.

Then, at 8.50 pm, at last he arrived; not DeGale, but the visitor they had all been waiting for: Charlie Fitch. Eighteen months after he had last officiated a world title fight, Fitch, a relatively inexperienced 43-year-old referee from Syracuse, New York, suddenly found himself inside the challenger’s changing room, aware of both the history and the importance of his role in this particular rivalry. He was aware, moreover, of what had happened to his predecessor.

“This is your referee… Charlie Fitch,” an inspector informed Groves as a group of men gathered around him. Handshakes then followed, the music was turned down, and the spotlight in the room shifted, if only momentarily.

“We’re going to go over the rules for tonight’s fight,” Fitch said, with Groves to his right, wearing boxer shorts and a T-shirt, and Fitzpatrick to his left. “You’re both championship fighters in a championship fight. There’s no ‘saved by the bell’ in any round. What that means is if a fighter gets knocked down and the bell rings, and the fighter doesn’t get up and I count to ten, they lose by knockout. In that situation, the trainer has to stay out of the ring until I make a decision to stop it or allow it to continue.

“The three-knockdown rule is not in effect, meaning if a fighter goes down three times in the same round, it will be at my discretion whether I stop the fight or allow it to continue. If a fighter gets hurt, but I can see he’s able to continue, I’ll let it go. Be careful with headbutts. I’ll look for any on the inside. And I don’t want to see any punches behind the head. The protector should be low enough so that I can see the navel. Punches above the beltline are okay. Anything below that beltline will be ruled a low blow. Can I see the protector?”

On cue, Fitzpatrick snatched his fighter’s protector from a table and handed it to the referee. “That’s a great one,” Fitch said, running his hands over it, admiring the quality of the leather. “It can even be slightly under the navel, that’s okay.” He turned back to Groves. “If you score a knockdown, go to the furthest neutral corner. If you guys get tied in a clinch, I want to see you work out of it. You can either punch your way out of the clinch or move out of the clinch. If I see the fighters unable to work out of it, I’ll give the command ‘break!’. Once I’ve said ‘break!’, you stop punching and break. I want a clean fight. You both know how to fight a clean fight and all these fans are here to see a good, clean fight.”

“May I ask a question?” said Fitzpatrick.

“Yes.”

“How will you react to punches to de back o’ de head?”

Fitch, judging by his expression, knew it was coming, therefore had his counter already cocked. “It will depend on the situation,” he said. “The fighter will either get a soft warning or a harder one. I may call ‘time’, go to the fighter and say, ‘Hey, no hitting behind the head,’ without taking a point, or I might go straight into calling ‘time’, bringing them to the centre of the ring and taking a point. I’ll make the right call at the right time depending on the situation.”

“Any other questions?” asked the inspector.

“No, jus’ de one I asked, thanks,” said Fitzpatrick.

Fitch shook Groves’ hand. “Good luck, man,” he said.

Later, Fitzpatrick removed his hands from his hips, approached the room’s flip chart, took a pen and, as though about to explain the complexities of the 4-3-3 formation when both in and out of possession, began to scribble on an A3 sheet of paper. Starting with bullet points, he went on to write “Mongoose”, “31” and “Dis-arm”. Then, for a moment, he paused. He rubbed his goatee beard and motioned for Barry O’Connell to join him. For a minute or so they conferred, after which the words “Religeous” and “Teach” were added to the sheet, the former spelt incorrectly.

Still not content with that, soon a second sheet was stuck to the wall with masking tape. On this sheet Fitzpatrick would take to drawing a large circle with the number “6” inside it, followed by the words “Vaya Con Dios” at the top, “No Ego” at the bottom, and “Rythm”, also spelt incorrectly, on either side. Meanwhile, on his third and final sheet, Fitzpatrick simply wrote “JAMES TONEY”, underlining it several times before, like Toney, standing back to admire his own work.

Fitzpatrick holds the pads for Groves (Jan Kruger/Getty Images)

PART III

Inside another needlessly large changing room down the corridor Carl Froch began skipping in an effort to stay warm and get a sweat going before hitting Robert McCracken’s pads. He had, by his own admission, been cold and dry when entering the ring to face George Groves in November – having only thrown half a dozen punches on the pads – and was this time eager not to make the same mistake. Skipping, therefore, was an essential part of the process.

His challenger, on the other hand, was to neglect skipping altogether. It wasn’t something he had ever done before a fight and so he could see no reason to start doing it now. Instead, as Froch skipped to get warm, Groves would just sing along to “All Along the Watchtower” by Jimi Hendrix, spit in the direction of the door, and then ask his lawyer, Neil Sibley, if he could go source some bananas from somewhere. After that, he passed his headphones to Jason Stevens, his old kickboxing coach, and began stretching against a table, performing high-kicks, low-kicks, and side-kicks. By 9.21 pm, he was then stepping inside his groin protector and his Union Jack fight trunks, adjusting both for comfort.

“What time do you want to glove up?” asked Fitzpatrick.

“We’ve got thirty minutes, yeah?” checked Groves, and Barry O’Connell, to confirm, nodded his head, sure of it. In that case, “I’m going to go look in the mirror,” Groves told the doctor, the trigger for yet another comical, Marx Brothers-esque scramble towards the bathroom.

Amused by the scene, Fitzpatrick shouted “vaya con dios!” and welcomed into the room Mick Williamson, the cuts man, who had just witnessed James DeGale stop Brandon Gonzales in four rounds. “Not sure about the stoppage,” said Williamson, laughing. “DeGale boxed well, but it was quick. Let’s just say that.”

Fitzpatrick rolled his eyes, haunted, perhaps, by an incident from November. He then pretended no such incident had ever occurred when Groves rejoined them from the bathroom.

“I heard DeGale won,” said the boxer.

“By stoppage,” confirmed his coach.

At 9.28 pm, the inspector was back. This time he had arrived with a pair of blue Grant boxing gloves and Groves, knowing these would soon be applied to his fists and would, a little later, be used for violence, looked to now change the mood in the room, swapping Tweet’s “Oops (Oh My)” for the more aggressive “Sail” by Awolnation. “Blame it on my A.D.D., baby…” he then mumbled, quietly, as one of the gloves covered his right hand.

“Nice?” said Fitzpatrick.

“Nice,” replied Groves.

“Niiiiiiice.”

The left glove followed and the inspector signed both at 9.32 pm. Seven minutes later, however, Groves was to realise there are certain limitations to wearing gloves prior to the act for which they were designed. That is to say, he no longer had the ability to control his phone and therefore the mood in the room. “You want the ‘sprints’ playlist,” he told me, having handed me his phone. “Then just hit play.”

The first song to play was “Hounds of Love” by The Futureheads and Groves, clearly feeling it, greeted its introduction with a burst of punches, each of them thrown in the direction of Fitzpatrick’s pads. In between these punch sequences Mick Williamson would grab a tub of Vaseline and apply the petroleum jelly around Groves’ eyebrows, ears, forehead, cheeks, and chin. He then slapped him on the arms to finish and Groves sipped from a bottle of water before asking: “Can you find ‘Dirty Diana’?”

Knowing it was needed, if just to maintain the equilibrium, it was with no small amount of alacrity that I searched the music library on the boxer’s phone and once finding the song immediately hit play. Yet somehow, to my horror, still the Arctic Monkeys’ “R U Mine” was dominating the room.

Groves, conscious of this, continued punching of course, but I could feel his eyes now on me and his brewing discontent. Worse, increasing in both volume and regularity were calls for him to leave the changing room, and even Fitzpatrick, his own coach, had started asking him if he was ready. It was time, no question about it, only there remained a suspicion that Groves wouldn’t be able to leave until he had heard this particular song. It was, you see, part of the routine, part of the ritual, part of him.

In search of it still, I then foolishly pressed stop, meaning nothing was now heard in the room except the sound of gloves hitting pads. “Put that song on, Elliot,” Groves said between punches, which, in the end, was what led me to explain the issue and what caused Groves to investigate; realising only in the process that he had yet to download the requested song. “Okay,” he said, resigned to it. “Put ‘PYT’ on instead.”

Unbeknown to Groves, outside his changing room in that moment were several Wembley Stadium officials and Sky Sports employees prepared to knock down the door and drag him out of hiding. What is more, Eddie Hearn, the event’s promoter, had arrived on the scene in a state of agitation, reminding anybody who would listen that there was a strict curfew time of 10.30 pm set by Transport for London. Elsewhere, pundits and commentators presumed mind games, stalling tactics on the part of a young man who had for months invested so heavily in psychological warfare.

Yet the reality is, the minor hold-up that night owed to nothing of the sort. Instead, if looking to blame anyone, blame it on my inability to complete a simple task. Or, better still, blame it on the boogie, for it was only once he had heard Michael Jackson sing that George Groves felt ready, properly ready, to leave.

George Groves rides a bus to take him to the ring (Scott Heavey/Getty Images)

PART IV

At 9.46 pm, the snarling and spitting and stoic challenger rushed down a corridor and blanked anyone who dared get in his way. He was, after all, late for a bus.

“It’s all well and good saying, ‘This is what I’ve dreamed about since I was a kid,’ but I don’t give a shit about all that bollocks,” he had told me three days ago. “It’s been life and death for the last eight weeks. I don’t give a fucking shit about a world title. It means nothing. I don’t even really give a shit about the money right now. I just want to win. I just want to win.”

Surrounded now by hefty minders and a team significantly larger than before, George Groves acknowledged not one of them as he arrived in the nick of time inside a Wembley Stadium parking lot. Nor, despite standing in front of a big, red, double-decker bus, laid on for him by his new management company, did he acknowledge the sheer absurdity of what was about to take place.

Those ignored, meanwhile, shuffled into the shadows to allow Groves to board the bus. Walking on ahead of him, they were soon to all sample both the noise and the faces awaiting the two boxers, the experience of which left no doubt as to what 80,000 fans wanted: violence. Give them violence, as well as a conclusive, brutal ending, and they seemingly didn’t really care who won; the commands of those leaning over the barriers alternating between “Fuck him up, Groves!” and “You’re getting knocked the fuck out, Groves!”

Eventually, when the bus slowly motored forward, the reticence with which it crept inside the stadium did a good job of matching the uncertainty of all involved. Fans, by that stage, were greeted not only by the bizarre spectacle of George Groves standing on its top deck, but all manner of fire jugglers and go-go girls were surrounding him, a setup too surreal even for David Lynch. It was, for all who witnessed it, a ring entrance like no other, choreographed by the very boxer now front and centre. (Over £50,000 of the budget, in fact, had been spent on both entrances at the insistence of the challenger.) Then, to the sound of Kasabian’s “Underdog”, Groves was seen making his way back to ground level and strutting down a short red carpet, by which time Prodigy’s “Spitfire” had kicked in, a reminder to us all that there was a fight about to happen.

Froch is on his way (Matthew Lewis/Getty Images)

As for Froch’s entrance, which started after Groves was in the ring, this, by comparison, was a rather low-key affair and consisted of no double-decker buses or fireballs. Froch, the champion, instead walked out to Queen’s “We Will Rock You”, a predictable singalong adept at getting bloodthirsty fans to stop booing, before arriving on the elevated platform to AC/DC’s “Shoot to Thrill”. A lightshow then promptly ensued, with lasers shooting green, blue, yellow and red all around him, and Froch, likely hating every second of it, began to shadowbox.

“George Groves and his team put a huge amount of effort into those ring walks,” said Eddie Hearn, the event’s promoter. “They had meetings on meetings down at Wembley for weeks leading up to the event. The event was so big you can lose yourself in what the fuck’s happening. And that’s why you have a team of people you trust and you let them get on with it. Carl Froch will say to me, ‘Whatever you think,’ not, ‘Right, come here, let’s go through everything.’ He’d rather go and spar 12 rounds than talk to me about fucking ring-walk music. I love that. We’ve sold Carl Froch on being a warrior, a man’s man, and someone who will fight anyone; not somebody who does great ring walks or does a dance and a jump over the top rope. He’s not that kind of person.”

Froch, in other words, took a backseat when it came to matters of triviality. He didn’t care for buses or acrobats. He didn’t even care for music. In fact, according to legend, Froch had to be cajoled into having any music at all by Matchroom’s head of media, Anthony Leaver, who, in the weeks leading up to the event, resorted to playing songs down the phone to Froch in the hope that he would stumble upon one, just one, he liked. Eventually he did, thankfully, only what followed ambivalence was overthinking, with Froch electing to knock back AC/DC’s “Highway to Hell” on the grounds that he didn’t want a boxing ring, his final port of call that May night, to represent hell. He liked the song, that much was true, but not the message, and for that reason it was struck off, replaced by “Shoot to Thrill”, a track and sentiment more aligned with his fighting ethos, he felt.

Similarly, Froch, once in the ring, offered to Groves no more than his back, completely ignoring the intensity of the challenger’s stare. This, a strategy planned, was something inspired by Middlesborough’s little-known John Pearce, a former Commonwealth Games gold medallist who had once performed the same trick on Froch in an ABA semi-final and sufficiently spooked him. Regardless, it was a bold, pointed move, and only when his T-shirt was taken off for the introductions did Froch at last turn around and face the centre of the ring. Their eyes then finally connected when referee Charlie Fitch called them together and said, “You both know the rules. Touch gloves now and come out fighting at the bell.”

Froch and Groves exchange punches (Scott Heavey/Getty Images)

PART V

“The best shot I’ve ever thrown in my life,” was how he described the finishing right hand, not yet certain it would also be the last. “I backed him into the ropes and he tried to throw that silly left hook, because he talked about the left hook, and I threw a fake and then threw a left hook-right hand,” Carl Froch continued. “The left hook had nothing on it, but George Groves tried to throw some sort of check-hook when the right hand came. Unfortunately for him he left his chin open and exposed and, because he was against the ropes, he had nowhere to go. I knew the punch was going to land before I threw it. It was perfectly in line. He could have ducked it but he didn’t have time.

“It was one of those punches where I was so relaxed when I threw it. I had my feet under me, the centre of gravity was perfect, and I just threw the punch without thinking too much about trying to knock him out. I just wanted to land the punch. It wasn’t until I dropped him that I knew he wasn’t getting up. I just thought, Yeah that hurt. But then I saw him on the floor with his ankle around the back of his neck and I thought, He’s in trouble here. He’s not going to beat the count. And if he does, it’s game over.”

Froch lands the finishing right hand (Scott Heavey/Getty Images)

The finish, it’s true, was about as conclusive as finishes get; the very finish, one could argue, the rivalry required. And yet, to the right of press row I could still hear a couple of women in expensive gowns scrutinising the debris, both unsure, despite the mess, whether their cravings had been fully satisfied. Careful, both, not to let the falling ticker-tape get stuck in their hair, as they watched Groves suck in oxygen on his stool one asked the other: “Did you enjoy it, babe?”

“Yes,” the other replied, “it was okay, I suppose. I would have liked to see some more hits, though. He got hit once and then that was it.”

“Yes. I’d have liked to see him take a few more big hits before going down as well. It happened very fast. Too fast.”

It was, I guess, a rivalry defined by three right hands – two in fight one, one in fight two – and concluded before the kind of audience that demanded, imagined and expected many more. An audience that, for the most part, cared little for the well-being of the fighters, nor their futures, so long as they witnessed the requisite number of “hits” to fulfil their deepest, darkest and most depraved desires.

If at all doubting this, consider how replays of the knockout punch on the big screens provoked whooping and hollering and high-fives and seal-claps from all those aroused by the prospect of hard punches and harder falls. Turn around and you could even see the inebriated re-enacting the finishing shot on each other, spilling buckets of beer in the process, as well as hear self-proclaimed experts illustrating to one another how they would have avoided the Froch right hand. “Should’ve kept his fucking hands up,” one advised, with others going so far as to boo and spit obscenities the way of the young boxer wearing the oxygen mask; the one whose bravery was that night matched only by his opponent’s.

Sure enough, by the time Carl Froch had tenderly placed his left glove on George Groves’ shoulder, pulled him close, and whispered words of scant consolation, the battered pair seemed the only humane ones among the 80,000 in the Colosseum.

Froch celebrates as Groves is consoled (BEN STANSALL/AFP via Getty Images)

PART VI

Some light relief: Come September, the England football team, still reeling from a rather dismal display at the 2014 World Cup, returned to a half-empty Wembley Stadium for an utterly pointless friendly against Norway. Watching what would become a 1-0 win that night was George Groves, a guest of Wembley, who, like many in attendance, soon became bored and left at half-time. Prior to kick-off, however, the boxer was seen leading his wife, Sophie, down the Wembley steps, admiring the pristine turf and, with his right hand, pointing at something in the distance. “See that spot over there, Soph?” he said, smiling. “That’s where I got knocked the fuck out a few months ago.”

Fire Walk With Me: Groves experienced it all that May night (Scott Heavey/Getty Images)

PART VII

Forty years before Froch vs. Groves II, another fighter named George was dropped in the eighth round by a right hand he never saw coming. He, too, probably felt he was winning the fight at the time (he wasn’t), and landing the heavier blows (questionable), and applying effective aggression (ineffective aggression would be more apt). Yet nothing, in the end, could interrupt or prevent what Muhammad Ali did to an exhausted George Foreman in Kinshasa, Zaire.

The defeat, Foreman’s first as a pro, would haunt him for years. It would motivate him to take the whole of 1975 off and would be the cause of a great, unshakeable depression. Of all the people to lose against, he thought, why that son of a bitch? He’d never hear the end of it, he feared. There would be reminders on every television screen and on every page of every newspaper and magazine. The punch, the fall, the putdowns, the chants, the history; it would all combine to add layer upon layer to Ali’s already considerable legacy and, in turn, compound Foreman’s enduring misery. They’d even probably make films about it. Books and all, each casting Foreman, this once-fearsome destroyer who bounced Joe Frazier off the canvas like a basketball, as the lumbering fool who fell for the “rope-a-dope”, the oldest trick in the book; duped not by “The Greatest” but by a supposedly old, slowing, and fading underdog.

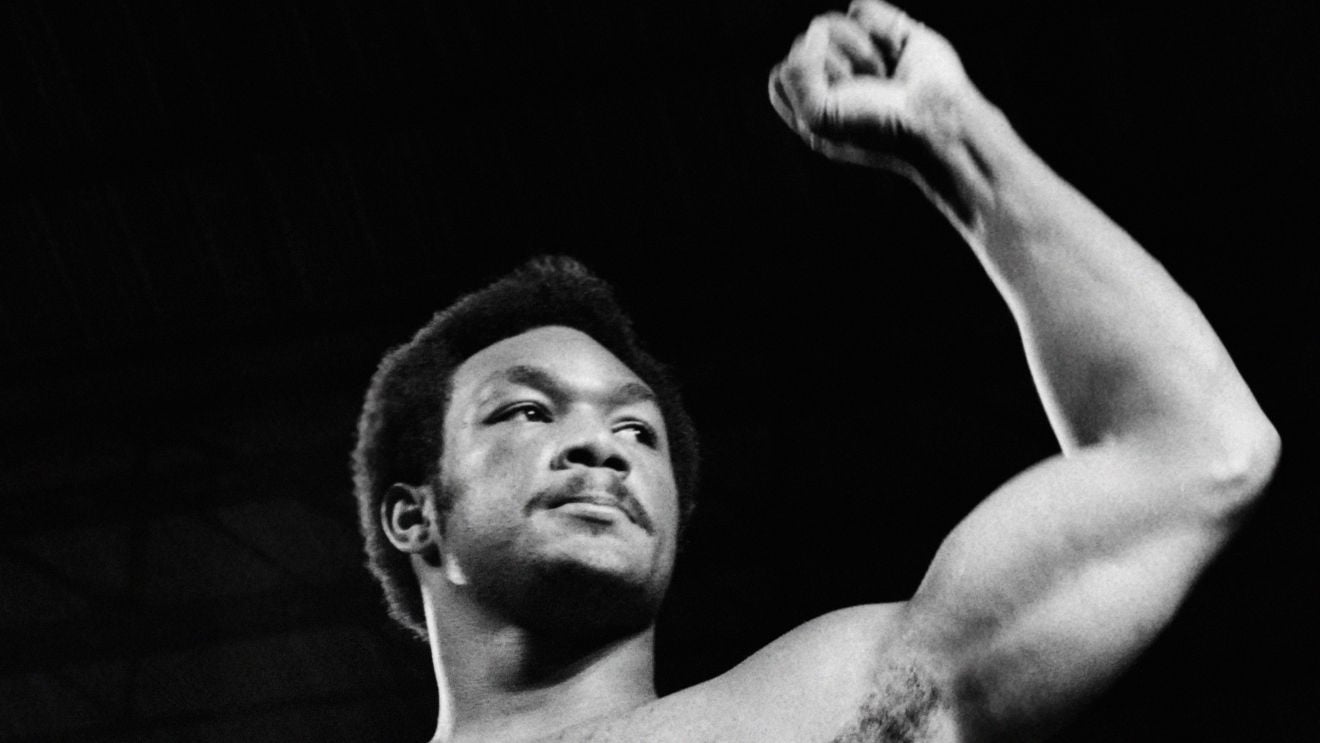

George Foreman (STR/AFP via Getty Images)

Mercifully, after losing again in 1977, this time to the slick Jimmy Young, Foreman claimed to have had in his locker room a religious experience so profound that he retired from boxing at the relatively young age of 28 (albeit only for a decade). By 1980, in fact, Foreman had become an ordained minister, byproducts of which were acceptance and forgiveness.

“I preached on streets all around the country, yet nobody recognised me,” said Foreman. “They didn’t care who I was. I cut my hair and my moustache. But one night when people were passing me by, I started preaching, ‘Yes, I’m George Foreman! I’m the one who lost to Muhammad Ali!’” People then stopped. They didn’t know who I was, but they came back and I confirmed I was George Foreman. I realised then that it was my name and my association with Muhammad Ali and ‘The Rumble in the Jungle’ that helped me with my ministry. So the one thing I’m now really proud of is that boxing match with Muhammad Ali.”

Along similar lines, Foreman’s publicist back then, Bill Caplan, once relayed a story to me about Big George that I later relayed to another George I believed could benefit from hearing it. It went something like this: “There’s a very famous picture of Ali knocking Foreman down in Zaire where he’s got one arm in the air and he’s kind of spiralling down to the floor. It was a ‘double truck’ in Sports Illustrated, which means two pages in the centre of the magazine. When people used to come up and ask George for his autograph, sometimes they’d bring that magazine and ask him to sign it and he’d say, ‘Oh please, I’ll sign anything but that photo. Give me something else.’ He’d say it good-naturedly, but he meant it.

“Anyway, he gave me the tour of his super beautiful home one day, which he and his wife helped the architect design, and we went into his office. In this office he had a huge monitor on his computer and his screensaver was that picture. I said, ‘George, that’s the picture you’d never sign and now it’s your screensaver on a living 52-inch monitor! I’m shocked!’ He said, ‘I look at that every day and it keeps me humble.’”

George Groves, driving his car home from the gym one afternoon in January, patiently listened to that story, though knew as well as I did that there was no need for him to at that stage be humbled. Just seven months had elapsed since he had been felled by Carl Froch’s right hand in Wembley Stadium and, to some extent, there was no need for him to even be reassured. Yet still, because reassurance is the only language an observer knows, I glanced at Groves for a sign; a sign he was listening; a sign he understood the meaning behind what was being said; a sign he could relate; a sign he would be okay. But, alas, nothing came back.

Joyce Carol Oates once wrote that “boxing is about failure far more than it is about success”, which, if true, is a truth one George grew to accept and a truth the other George, twenty-six and again mandatory challenger for a world title, was for now, like any twentysomething, too young, too feisty, too hungry, too ambitious, too knowing, too naïve, too emotional, too brave, too arrogant, too ignorant, too proud and too hurt to properly hear, let alone understand. Which is why, rather than bore him any further, I chose to keep that quote to myself, allowing George Groves to swerve the topic of George Foreman altogether and speak instead of his longstanding admiration for Muhammad Ali. It was, I sensed, easier that way. At least for now.

Content: George Groves in retirement (David M. Benett/Dave Benett/WireImage)