By the time the year 1967 rolled around, Emile Griffith was on top of the boxing world. As a former three-time world welterweight champion and current middleweight title holder, Griffith’s credentials put him on a par with many of the all-time greats.

One of the busier fighters of his era, it took a court order to prevent Griffith from being both the world welterweight and middleweight champion simultaneously. Only weighing 151lbs when he dethroned Dick Tiger for the middleweight crown, Griffith could have still made the 147lbs welterweight limit to defend that title.

In succeeding fights, Griffith would frequently weigh-in under the junior middleweight 154lbs limit as well, But there was no serious consideration to him campaigning in that weight class due to the lack of significance it held during that time. But Griffith was doing just fine ruling the middleweights, making two successful title defenses against New Yorker Joey Archer, before agreeing to defend his title against Italy’s Nino Benvenuti on April 17, 1967 at the old Madison Square Garden.

Despite having impressive credentials, Benvenuti was lightly regarded entering the contest, this in large part to the stigma that hung over European fighters at the time. Although they occasionally came to the United States and had success, such as France’s Marcel Cerdan stopping Tony Zale to win the middleweight crown, for the most part the forays of the Europeans did not end well.

That Benvenuti’s challenge was not taken more seriously at the time is baffling on reflection. At the Rome Olympics in 1960, he was voted as the best boxer of the tournament, beating out a teenage phenom named Cassius Clay. Benvenuti was also a former world champion as well, winning the junior middleweight title from fellow Italian Sandro Mazzinghi, then making two defenses of that crown, before dropping it on a split decision to South Korean, Ki Soo Kim in Seoul. Benvenuti had only lost once in 72 fights, and had beaten credible opposition such as Don Fullmer and Denny Moyer among others.

In this age of social media, Benvenuti would have been fully exposed to the public who would recognise the threat he posed to Griffith, but at the time few people attending their fight at Madison Square Garden had seen Nino box. Griffith was another matter. He had fought so many times in Madison Square Garden, that his manager/trainer, Gil Clancy, described it as the house that Griffith built. Griffith was also well known outside of the boxing community primarily because of the ill-fated match with Benny Paret five years previously. Paret’s death had a profound effect on the sport with many calling for it to be abolished due to its brutality. Some said that Griffith was never the same in the ring afterwards, that he eased off on his punches because he was haunted by the spectre of Paret’s death. While it is easy to surmise such a theory, the truth is that Griffith was more of a grinder than a puncher. His keys to victory were a high workrate, his physical strength, and fundamentally being able to do things better than his opponents. As Clancy said, “Griffith did nothing great, but he did everything well.”

Although Griffith knocked Tiger down for the first time in his career during the ninth round of their fight, the Nigerian rebounded and some thought was unfortunate not to be given the decision. The two title defenses against Archer were also close. The first one could have easily gone to Archer, which actually might have aided Griffith’s legacy in that he would then have regained the crown in their rematch instead of just retaining it. A three-peat of the middleweight title to match what he did at welterweight, would have made Griffith truly immortal if he is not considered so already.

Although he was born in the Virgin Islands, Griffith lived and trained in New York, where he continued to reside for the rest of his life. He was a New Yorker and a crowd favorite, but on the night of April 17, 1967 at MSG, Emile was startled by the noise level directed toward his opponent. New York boasted a huge Italian population who came out in force for Italy’s Benvenuti, making themselves heard unlike any other night that Griffith fought. “Nino, Nino, Nino” their voices rose in unison from the rafters all the way down to ringside.

The Garden was rocking. The noise reached a fever pitch when Benvenuti dropped Griffith heavily on his backside in round two. How hurt Griffith was he only knew, but what is indisputable is the stunned look on his face as he lay on the canvas before getting up a few seconds later. It was Benvenuti introducing himself to the American audience at Griffith’s expense.

Benvenuti, 28, spoke no English, but he was oozing with charisma, a matinee idol, handsome, and long hair that was pronounced. He was a boxer-puncher. who liked to dart in and out, not adverse to using tactics that stretched the rules a little, but at the same time would look toward the referee if he felt victimised.

Benvenuti’s strong start had the Garden in an uproar, but disaster nearly struck in the fourth round when Griffith delivered a thunderbolt, a right hand that sent Benvenuti down and sprawling along the ropes. Nino was badly hurt with more than enough time in the round for Griffith to finish him. Later, Griffith would put the blame on himself for Benvenuti escaping the crisis. “I went right hand crazy,” he said. It is hard to fathom what would have become of Benvenuti had he not survived the round. Perhaps he would have regrouped and won the title at a later date, but his career as we know it and his rivalry with Griffith never would have materialised.

From the fifth round on it was basically Benvenuti’s fight. Griffith moved forward, but could never get comfortable. Benvenuti darted in and out, rushing the Virgin Islander who could not get off. When the final bell rang it appeared that Benvenuti had done more than enough to take the title. The judges concurred in scoring it unanimously for him by margins of 10-5, 10-5 and 9-6.

Ring Magazine voted it the ‘Fight of the Year’, but that was more a result of the stir that Benvenuti’s victory caused. The action inside the ring from the fifth round on was not especially exciting. This was reflected by the blow-by-blow account of the legendary broadcaster Don Dunphy. Criticised as to why he did not show a touch more enthusiasm, Dunphy said, “I won’t fake a fight call.”

Italy rejoiced. If Benvenuti was not a national hero in his country before he certainly was now. In 11 days, Muhammad Ali would refuse induction into the United States military. His license to box was suspended. The sport needed a shot in the arm. Benvenuti provided that. He was now a genuine star in his own right, whose victory over Griffith was not regarded as a one-off. The day after beating Griffith, Benvenuti was interviewed alongside Rocky Marciano who said, “Last night I did not see a good fighter, I saw a great one.” Nino was the talk of the boxing world.

It was generally reported that Griffith had taken a beating in the fight. While that might have been a slight stretch, there is no question that his pride was deeply hurt to the point of being bitter. Griffith knew how poorly he had performed by his standards. He had something to prove in the rematch which took place on September 29, 1967 at New York’s Shea Stadium, the big outdoor ballpark that served as the home to the New York Mets and New York Jets.

Benvenuti’s victory in the first fight was decisive enough for people to question how much more Griffith could do to turn the tables in the rematch. Griffith had lost before, but there was a resolve to avenge this defeat like there had never been previously. When asked how he would defeat Benvenuti, Griffith got right to the point. “I’m gonna knock him out,” he said confidently. Clancy wasn’t so sure. Clancy knew that more likely than not they would go to the scorecards again. “I want judges who won’t be influenced by all the chants of Nino, Nino,” he said.

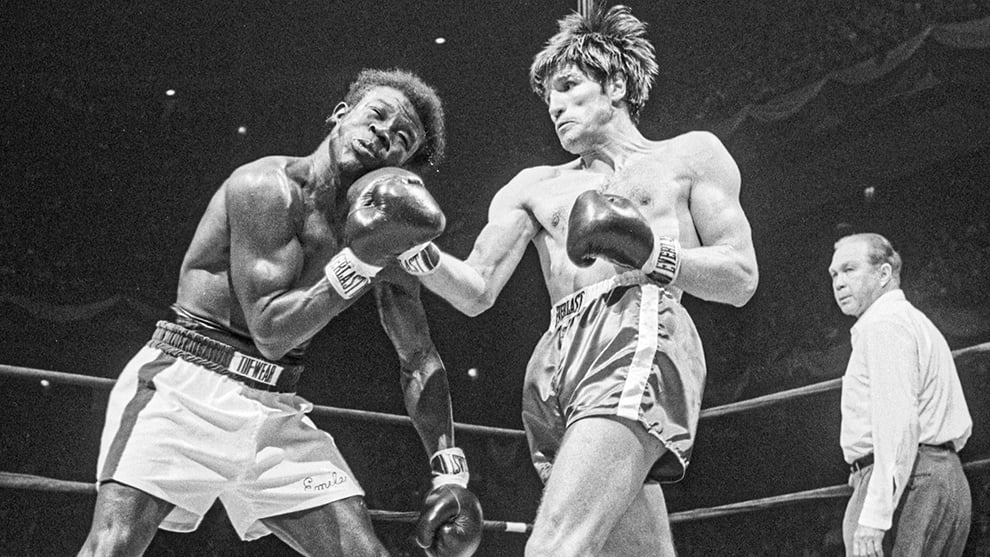

(Original Caption) 3/7/1970-: Nino Benvenuti is tensed up as he delivers a right to the jaw of Emile Griffith during their 1968 title bout. Nino challenged and won the crown.

Griffith was more focused the second time around, controlling the match by staying a gentle step ahead of Benvenuti throughout. Griffith would work his way inside where he scored with uppercuts while smothering Benvenuti’s attack. But Benvenuti landed the occasional jarring hook which kept him in the fight. It was not until Griffith dropped Benvenuti in the 14th round that it became apparent that he would regain the title. Yet, according to one scorecard, 7-7-1 he didn’t, but the other two came in at 9-5-1, giving Griffith a well-deserved victory. By the way, the rules at the time said that if a judge had the fighters even at the end of the fight he should break the tie by going to the supplemental point system. Mysteriously, the judge failed to give Griffith credit for the knockdown he scored, making it officially a majority decision instead of a unanimous one. No matter, Griffith rejoiced.

Afterward in his jubilant dressing room Griffith’s mother, a big strong woman, picked up her son and held him in the air like a baby. Emile, who was always a momma’s boy, grinned widely. “I had to show a lot of so-called friends that I was better than Nino,” he said.

Griffith’s victory restored order, not only in the middleweight division where he once again reigned supreme, but in his head-to-head comparison with Nino. As a result, he was favoured to win the rubber match. The new Madison Square Garden (the one of today), opened on March 4, 1968 with a doubleheader featuring Griffith and Benvenuti as the co-main event along with Joe Frazier vs Buster Mathis.

Both Griffith and Frazier set up camp for their respective fights at the Concord Hotel in upstate New York. The two became great friends.

Griffith trained hard as always and was in great form going into the fight. The same could not necessarily be said about Benvenuti.

Interestingly enough, both took a tune-up match in Italy, during the interim. Griffith had little trouble disposing of Italy’s Remo Golfarini in six rounds. Benvenuti struggled, needing to come on in the second half of the match to win a 10-round decision over American, Charley Austin. But Benvenuti remained confident and took issue with those who felt he was decisively beaten by Griffith. “My second fight with Griffith was very close,” he opined.

Clancy had described Griffith as a fighter who did nothing great, but everything well. If Griffith’s greatest asset was his enormous strength, his biggest drawback was his tendency to get lackadaisical from time to time. Admittedly, it drove Clancy crazy. He would try to wake Griffith up from his stupor by slapping him hard across the face as the fighter sat on the stool in the corner. In this day and age, such an action would have evoked a tremendous uproar, but at that time it was not seen as anything outrageous. The men had been together from the time Griffith had started to box as an amateur. They reportedly never had a contract, doing all of their business dealings on a handshake. The two genuinely cared for one another. Clancy’s partner Howie Albert who also served as Griffith’s co manager and cornerman, formed a tight knit unit.

Benvenuti got off to a fast start in the third encounter. He was generally beating Griffith to the punch and was faster on his feet than he was in the last match.

In the ninth round, Benvenuti dropped Griffith in a heap with a right. It was a hard, solid blow that hurt the defending champion. Emile quickly recovered, but at that point everyone knew his title was in serious jeopardy.

At the end of 12 rounds, Benvenuti appeared to have a commanding if not insurmountable lead. Griffith furiously rallied over the last three rounds, creating high drama in the last minute when he hurt Benvenuti with a right that had the challenger reeling. Griffith desperately tried to finish the job, but ran out of time not only in the round, but on the final scorecards, losing a unanimous decision by margins of 8-6-1, 8-6-1, and 7-7-1 (points 9-8 Benvenuti). The decision in Benvenuti’s favour was not controversial, the closeness of the scorecards withstanding. Even Clancy who veteran boxing aficionado Lew Eskin once said never agreed with a decision that went against one of his fighters, did not claim they were hard done by the verdict. Instead, Clancy lamented what took his man so long to get going. Griffith though disagreed, convinced he had won, later saying, “If they had given me the decision, Benvenuti’s fans would have torn down Madison Square Garden.”

A fourth fight was not ruled out, but never quite transpired. The closest it came to happening was the following year when Griffith avenged a highly controversial loss to Philadelphian Stan ‘Kitten’ Hayward. Entering Griffith’s dressing room afterward to help take his gloves off was old friend Benvenuti. Although Griffith won decisively on points, Garden Matchmaker Teddy Brenner felt that he lacked spark. Brenner put off the notion of a fourth fight with Benvenuti until it gradually faded away.

Griffith would go on to score many fine victories in the succeeding years and receive four more cracks at a world title, never winning it. He dropped down to welterweight to challenge the great Jose Napoles for his old welterweight crown and was beaten decisively on points. Twice Carlos Monzon turned back Griffith’s challenges. The first by a 14th round stoppage when Griffith, behind on points, doubled over due to leg cramps. In their rematch, Griffith was beaten on the cards by two, three and four points respectively. According to Clancy, British promoter Mickey Duff peaked at the scorecards before they were announced, then hurried excitedly over to him and said, ‘The old man did it, Griffith is champion again.” Not quite, officially at least.

Afterwards, Monzon said that it was the toughest match of his career. Three years later, when he was on the downside of his career, Griffith’s name was enough to get him one last chance at a world title when he challenged Eckhard Dagge for the WBC junior middleweight title in Germany. Griffith got himself into supreme condition and turned back the clock to an extent, appearing to hold a slight lead at the end of 15 rounds. But Dagge, boxing in his home country, was awarded a majority decision.

After defeating Griffith the second time, Benvenuti performed erratically in non-title matches, losing a couple and boxing a draw, but with the title on the line he was his old self, successfully defending it four times before being knocked out by Monzon in 12 rounds in November of 1970 in Italy. It was a result which no one saw coming. In the rematch, Benvenuti fared worse, being halted in three. That would be his last fight.

Because of the Paret tragedy, Griffith’s legacy will always be linked to him more than any other opponent. Not so for Benvenuti. Griffith was far and away his greatest rival, the one who brought out the best in him, the one who always invoked the warmest memories. Their bond would turn into a lifetime friendship outside of the ring until the day Griffith died in 2013 at the age of 75. So close were the two that Griffith was Benvenuti’s son’s godfather.

Benvenuti would go a step further, periodically flying Griffith to Italy where the two men sat with a crowd of people who watched the tapes of their fights. And, according to Griffith, he had quite a bit of support in Benvenuti’s homeland.

Former world middleweight champion Vito Antuofermo can vouch for that. As a young teenager living in Italy who had not yet laced on a glove, Antuofermo stayed up late to watch the Benvenuti vs Griffith fights. “They were both my idols, maybe Griffith a little more so,” he once told me. Antuofermo never imagined that one day he and Griffith would share a ring at Madison Square Garden and that he would win the cherished middleweight title that both of his idols held.

Obviously, Ali vs Frazier is the greatest trilogy in boxing history. But, aside from that, there has arguably never been another three-fight series in which the fighters were as evenly matched and stirred the emotions of the public as did Benvenuti and Griffith.

At the age of 86, Benvenuti is the oldest former undisputed world champion alive today. But the mention of his name always invokes the memories of the Griffith fights first and foremost. Neither could have been given a more worthy adversary than the other.